Restorative Conversations:

Expanding the Dialogue

January 2018 - April 2019

In partnership with NS Advisory Council on Status of Women, Mi’kmaw Legal Support Network and Bridges Institute

Funded by: Justice Canada, PCVI

The NS Advisory Council on the Status of Women, in collaboration with key community-based organizations, engaged a broad grouping of community organizations advocating for victims and those offering restorative approaches in a structured exploration of how a restorative approach can support better justice outcomes for victims of gendered violence. This exploration will be supported by input from an international learning community of restorative justice scholars and will be further strengthened by the development of an action research framework that will allow for continued further work.

Focus was on three key spheres of action: Research and knowledge mobilization; Facilitated dialogue and asset mapping; and collaborative illumination of principles to guide future action and ongoing evaluation.

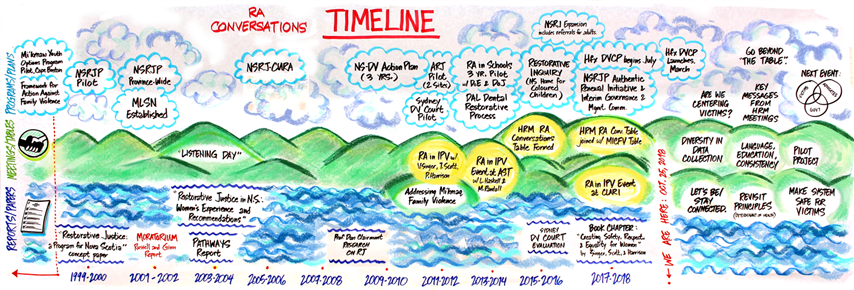

Nova Scotia has a unique history taking a restorative approach to justice, having established a comprehensive restorative justice program for youth in 2000, and that recently expanded access to this program to adults in 2016. Additionally, Nova Scotia has supported the development of a community of practice in schools using a restorative approach to both build community and support disciplinary responses that allow effective reintegration of students. Supporting this is an active Academy examining this through the lens of relational theory. Led by Professor Jennifer Llewellyn, the Schulich School of Law has been the nexus for an international learning community engaging scholars from New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States to consider the role of a restorative approach grounded in relational theory to build sound public policy to address complex problems.

However, there remains an important gap area in this work with respect to access to these processes for victims of gendered violence, an area where active and engaged victim support and advocacy work is the strongest. With a moratorium in place restricting the use of these processes, the only resolution pathways available to support these victims is the formal criminal justice system which struggles to meet their needs. It is important to recognize that this long-standing restriction was based on a commitment to work to ensure best outcomes for victims and concerns that informal community-led models such as the Nova Scotia Restorative Justice Program might not be robust enough to ensure the safety of victims of these crimes.

Recently, at the community level, organizations working in the field of gendered violence have begun to explore how less offender-focused processes might be able to safely play a role in building more meaningful justice for victims of gendered violence, and have begun to seek those places of common ground which focus on the shared awareness that the current criminal justice system does not serve victims well and most especially is not able to meet the justice needs of victims of gendered violence.

This project embraced the value of these important early conversations and supported them through research and knowledge mobilization, facilitated exploration and asset mapping, and collaboratively illuminated principles needed to underlie any action steps of future work in this area.

This project unfolded at a very opportune time as this dialogue was undertaken in concert with significant efforts within both government and the independent bodies of the criminal justice system to envision transformation of the system to change access to justice, achieve stronger accountability outcomes, and address other flaws of the system. Indeed, the decision to expand to an Adult Restorative Justice program was directly related to this work, as have been significant improvements to the Maintenance Enforcement legislation that better support just outcomes for women and children. Work is also proceeding to expand the Province's Domestic Violence Court Program and Mental Health Court Programs, so this is a time of innovation and the consideration of the specialized needs of populations that come before the courts. The Province is also leading breakthrough work through the Restorative Inquiry in to the abuses suffered by residents of the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children.

There is also great importance in finding the right space for this exploration. Trauma-informed models of practice point to the need for autonomy, control, context, resolution, a community of support, and future focused pathways for healing as part of an experience of resolution, all of which could potentially be outcomes of a restorative approach. The cautions raised in 2000 by the women’s advocacy community remain real: these are crimes that are fundamentally about power and control and, while on a continuum of harms, often place the victims at the highest risk.

The challenge is to collaboratively define what can be crafted that is both protective of those who are victimized and offer them a way forward that is more contextualized and that focuses on both accountability and autonomy of choice for victims. The fact that over twenty organizations have flagged their openness to be engaged in this dialogue is indeed promising.

There is a tendency as well, to define the process of a restorative approach as only valid as a tangential contributor to the wider criminal justice response and imagined only in the context of the transactional engagement of a victim and offender as they in some way explore and find accountability in regard to the criminal act itself, rather than trying to imagine what a more trauma-informed, restorative approach might look like across systems that offer supports to victims of gendered violence. This is where a research framework and knowledge mobilization will assist in building a shared awareness of possibilities and approaches.

It is important as well to lift up and more deeply understand the work unfolding in Nova Scotia Aboriginal communities, which have embraced, through a customary law lens, a community accountability process for these gendered violence crimes which has been identified as an asset by the courts. While responding to a small range of cases, they are nonetheless developing a collaborative and principled approach which places focus on the offender and the community. This project will intentionally explore this work to more deeply understand how the role of community accountability and interagency collaborations has addressed to some degree the concerns surrounding these processes. This work will also honour the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action and explore how to both support and more fully promulgate this work.

The plan to integrate the development of an action research framework into this dialogue initiative allows for sustainability of the work under this project, as it will lay out the pathway for how the principles arrived at can be the foundation for next actions. It will also support the broad dissemination of findings in innovative ways, using a variety of media, to enlarge the community of practice using and developing proficiencies in these approaches. By further expanding the dialogue and sharing the outcomes of this very deliberative and thoughtful year of research, examination, and mapping, we may collectively find a way forward for more just outcomes for victims of gendered violence that is respectful of and makes space for their autonomy and choice.