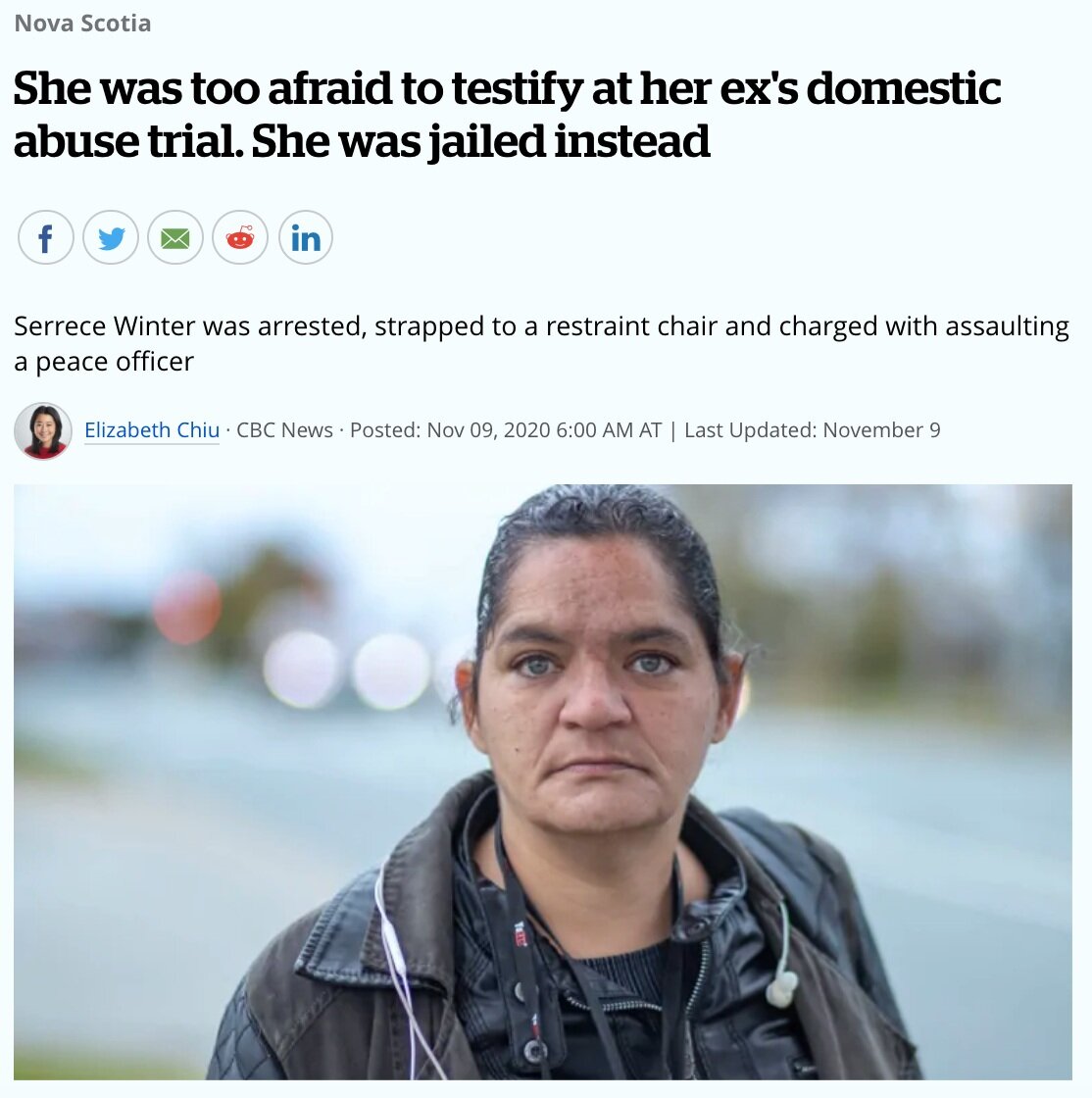

We at Be the Peace Institute are outraged by the recent CBC story about Serrece Winter who was arrested after a judge issued a warrant (at the request of the Crown) when she did not appear in court to testify against her violent abuser. We are deeply disturbed by the failure of an appropriate police or judicial response to a victim seeking help and a legal resolution for crimes committed against her. Instead, she was jailed, restrained and terrorized with excessive use of force by more than 5 police officers even as it was being captured on video. This showed a complete disregard for her legal and human rights, a lack of understanding of the complex trauma response of gender-based violence and without any offer of either medical, legal or mental health assistance. How can we continue to justify the criminalization of women who come forward for harms committed against them while simultaneously criticizing them for not leaving, for not reporting, and for not showing up in court?

There are a multitude of reasons why she might not appear in court to face her abusive ex-partner including, as she explains in her own words, she was simply too afraid to testify. It continues to be a minority of cases where testimonial aids like closed circuit televised testimony or use of screens or barriers are allowed in the court room as it is the legal right of the accused to face their accuser. But what about the Victim Bill of Rights, and the rights of the abused? It is no wonder survivours of gender-based violence come forward at staggeringly low rates.

Not only did her immobilizing fear of her abuser prevent her from testifying, land her in jail and violently restrained by police, it also was reported that the charges against her abuser were dropped, the Crown determining there was no realistic prospect of conviction. The only thing standing between Winter and further violence at his hands is a time-limited peace bond.

These burdens placed on victims of gender-based violence need to stop. Among other reforms needed, we join our colleagues at Women’s Centres Connect in their call to abolish the use of bench warrants, (issued by a judge for the arrest of a person who has failed to appear at a hearing or trial).

We have been a partner in a research project, Weighing Justice in NS, examining the pro-arrest, pro-charge, pro-prosecution policies in responding to domestic violence. While they encourage an arrest, charges and prosecution, the reality remains that if a victim declines to testify, for any number of legitimate reasons, the rate of case collapse is high. This puts her at further risk when he is released with potentially few consequences and little monitoring other than a possible peace bond, even in high risk situations like Ms. Winter’s.

Given that the system as it is cannot guarantee her safety, there must be other ways to prosecute the case and achieve accountability when the victim is too traumatized to appear. In other complex cases, including homicides, there may be no victim who can testify. Yet these go forward by relying on other witnesses to build the case.

As a Black and Indigenous woman who suffers from PTSD and bipolar disorder, Winter’s likelihood of experiencing deeper, systemic injustices increases. Each of her social and cultural identities in and of themselves put her in an increasingly vulnerable position. At the intersection of her race, gender, class and compounded by her mental health issues, the responses of our oppressive patriarchal and colonial legal system are exposed.

We have long seen the need for specialized mental health experts to be integrated into a trauma-informed police response. These professionals can skillfully provide ongoing and appropriate support to address acute trauma, self-harm, addictions and other mental health related issues in preventing further harm to an already vulnerable and traumatized person.

But what is truly disheartening is how this continues to happen despite all that we know. Even as police and the justice system are under increased public scrutiny on how they handle cases of gender-based violence as well as how they treat people of colour and those who struggle with mental illness - how does this continue to happen??

We know that the time after reporting or leaving an abusive relationship is statistically the most dangerous and vulnerable time for a survivor. According to the Canadian Women’s Foundation 26% of all women who are murdered by their spouse had left the relationship and half of the murdered women were killed within two months of leaving the relationship. Yet this is when a survivor is often faced with the most complexity and the least amount of navigation assistance in grappling with the trauma of the criminal justice system response (and potentially family court and child protection intervention if children are involved). These systems all over-responsibilize the very person who has been traumatized by the abuse. No such similar pressure is placed on the abuser, even in high risk cases.

Enhanced police training, increased resources and innovative initiatives in Nova Scotia have followed acknowledgement that the mainstream system is routinely failing survivors of gender-based violence. But when legal and human rights so readily go out the window, we know there is more work to do.

While our criminal justice system is founded on some basic tenants of due process and equality before the law, gender-based violence continues to be the only crime where more often than not, reporting it only serves to incite more harm than the crime itself, especially for people from minoritized groups.

We need a public reckoning. We must stand with our Black and Indigenous sisters against these injustices and call out those accountable to do better and demand nothing less.

Contributed by Stacey Godsoe